Analyzing Third-Party Risk in Open Source Software

Third-party risk management is an important part of protecting your organization. But how do you manage the risks of open source software when you have no vendor relationship?

February 25, 2025

Your business depends on third parties — your suppliers, utility companies, possibly delivery services, and so on. Your business’s software depends on third parties, too. Even if you have an in-house development team, they’re probably using software-as-a-service and infrastructure-as-a-service platforms, open source and vendor supplied libraries, operating systems, and so on. If you’re not already managing your third-party risks, CSO Online says this is the year to start.

If you are conducting third-party risk management, then you know it’s the process of examining and mitigating risks from your vendors, contractors, partners, etc. But most third-party risk management is focused on commercial relationships. You have contracts in place that put requirements on your third parties and include some form of relief if they don’t meet their obligations. What happens with open source software, where the software is provided as-is and you have no contractual relationship? Many of the general concepts remain the same, with some differences in how you mitigate the risks.

Analyzing third-party risk in open source software

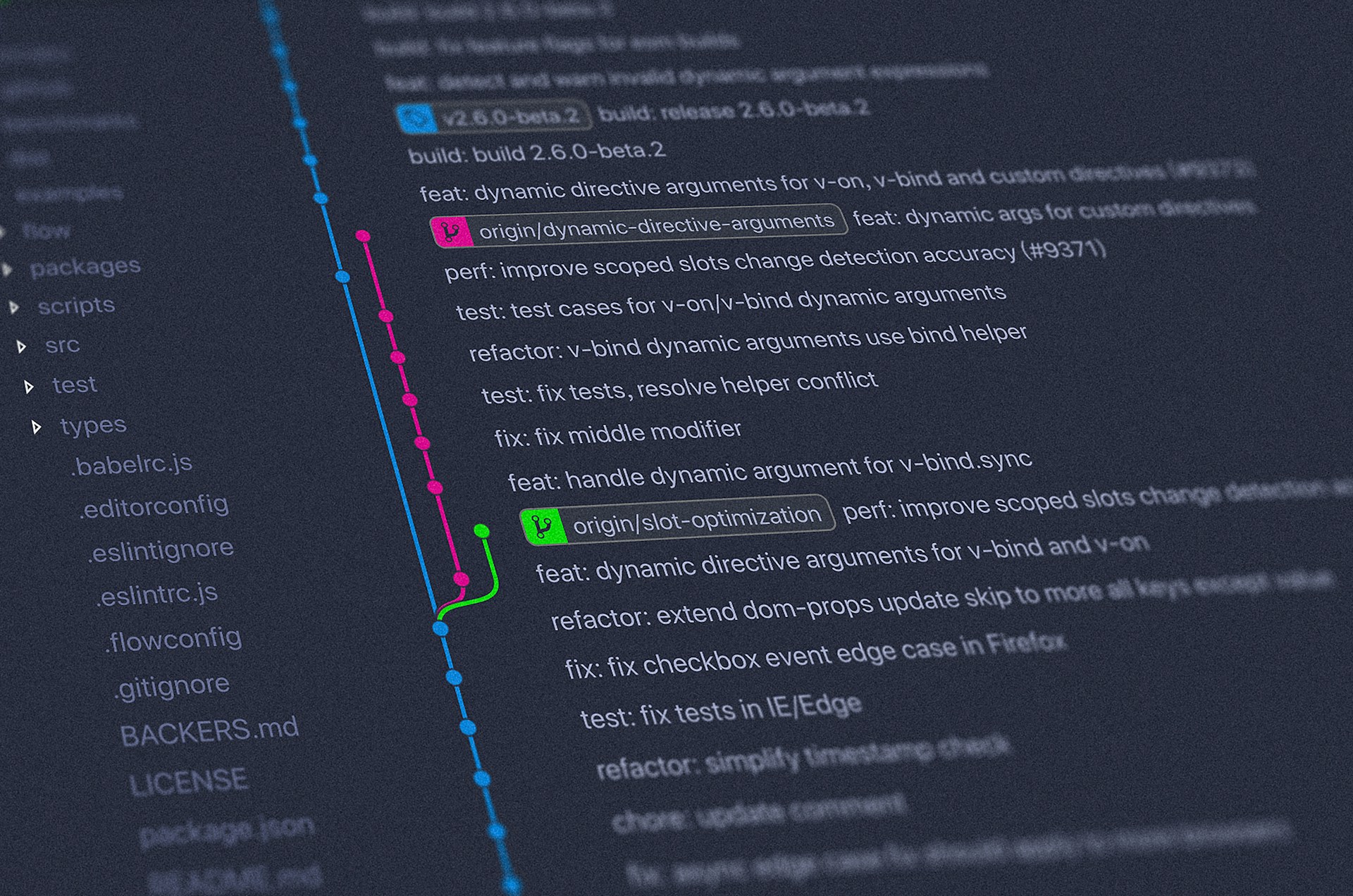

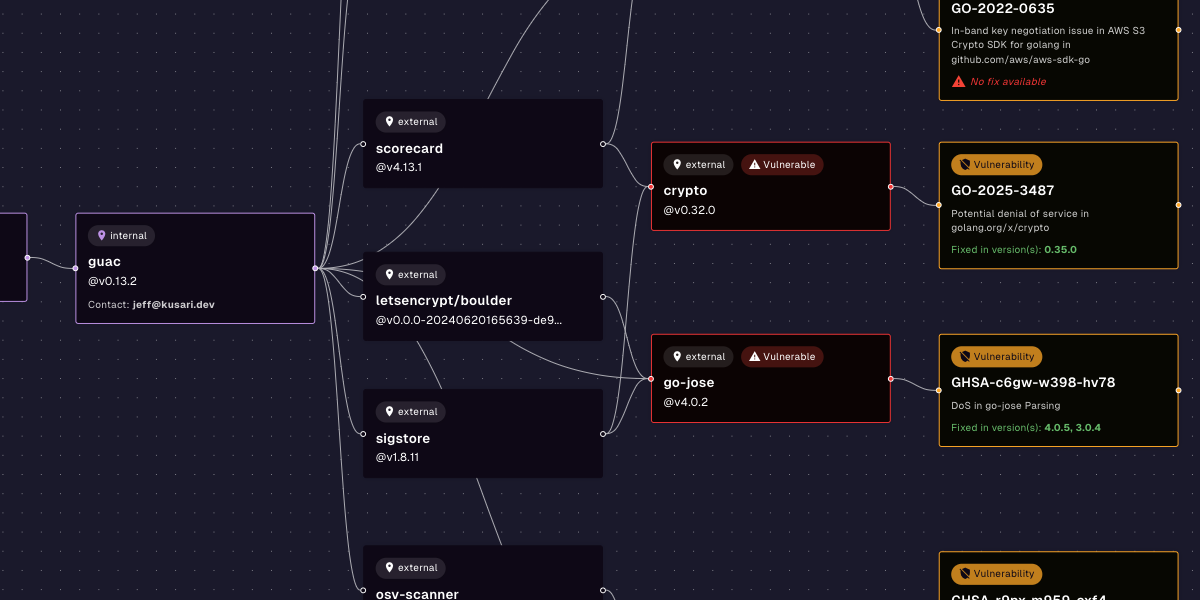

The most common focus when analyzing open source software risk is vulnerabilities. This makes sense since it’s an immediate-term concern. Just like with your vendor-supplied software, a vulnerability in an open source library or tool can result in significant financial and reputational harm. You should absolutely check your direct and transitive open source dependencies for vulnerabilities so that you can prevent them from reaching production or fix them quickly if they do.

But when you’re evaluating whether or not to bring a library into your dependency graph, the vulnerability count at that given moment doesn’t tell you what undiscovered vulnerabilities currently exist or what vulnerabilities might exist in the future. Vulnerability count — and severity — is one part of the risk analysis, but you can’t stop there.

One factor in your ability to quickly remediate future vulnerabilities is the responsiveness of the upstream project. After all, you can’t apply a fix that doesn’t exist. With established projects, you can look at their track record. Do issues, especially security issues, get fixed quickly or do they linger? Do the maintainers acknowledge issues quickly or do reports sit un-triaged? A project that is more responsive to issue reports will usually be fast to fix vulnerabilities, making them lower risk.

A project’s responsiveness will, in turn, be related to the size of the developer community. A single-maintainer project relies on one person to be available. If they’re not available for whatever reason, then the issues won’t get fixed. A larger pool of maintainers lowers the risk from any one person needing to step away from the project. This isn’t just a factor in reducing the security risk, it also reduces the risk that the project gets abandoned.

If you’re thinking that an abandoned project is a security risk, you’re correct. But it’s a risk in other ways as well. An abandoned project won’t get new features that you might need. It also won’t be updated to be compatible with changes in the ecosystem around it. If hardware architectures change or if the underlying language reaches end-of-life, abandoned projects won’t be updated to keep compatibility. This is not a hypothetical concern; Apple switched their Mac offerings from PowerPC processors to Intel processors to in-house ARM processors in a 15-year span and Python 2 reached end of life in 2020, necessitating a switch to Python 3 or another language entirely. If your dependencies don’t update for changes in your stack, your ability to develop new features is going to be stuck.

A related consideration is whether or not the project provides an explicit support period for releases. Many projects never formally die, the maintainers just drift away over time. It’s not always clear if a stagnant project is fully abandoned or if it’s just in good shape and doesn’t need much attention. If a project publishes an explicit support period, that provides no guarantee, but it shows that the project at least intends to continue providing support through that time.

The final category of risk that open source projects can introduce are legal risks. Although open source software is publicly available and typically available without payment, that doesn’t mean that you can do whatever you’d like with it. Open source licenses carry a variety of obligations; some require attribution, some require that you provide the source code of derivative works under the same license. Some licenses include an explicit grant of patent rights, others are silent on the matter. You may also need to change logos or other trademarks before you distribute some applications.

In the next post, we'll cover how to address the risks you find.

Previous

No older posts

Next

No newer posts

.webp)

.webp)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)